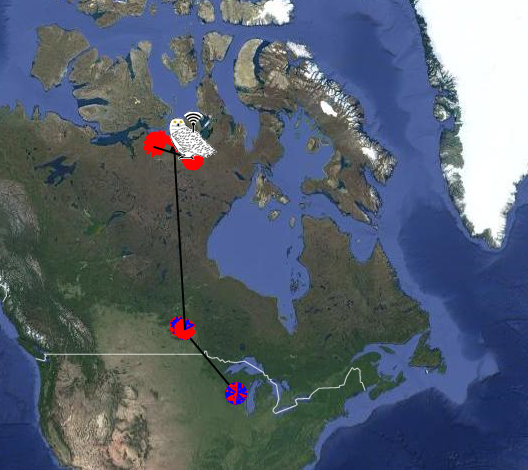

WSO has joined forces with other funders to support the electronic tagging of as many as six Snowy Owls in Wisconsin this winter as part of a multistate effort known as Project SNOWstorm.

More than 50 owls have been tagged in 10 states from North Dakota to Maine since 2013. WSO earlier funded transmitters for two of the six owls tagged in Wisconsin during previous winters -- for a bird known as Buena Vista in 2013 and for Kewaunee in 2014.

More than 50 owls have been tagged in 10 states from North Dakota to Maine since 2013. WSO earlier funded transmitters for two of the six owls tagged in Wisconsin during previous winters -- for a bird known as Buena Vista in 2013 and for Kewaunee in 2014.

With more than 200 Snowy Owls recorded in Wisconsin already this winter, public interest in these charismatic and nomadic Arctic visitors has led to generous support for Project SNOWstorm, which employs cutting-edge technology to track North American owls’ movements in astounding detail, and for years at a time.

This year, WSO is supporting an additional transmitter, probably for an owl to be trapped in the lower Green Bay area. The Madison Audubon Society and the Wisconsin Public Service Foundation each are funding a transmitter, while a crowd-funded campaign by the Natural Resources Foundation of Wisconsin raised enough, along with NRF’s match, to support two transmitters. The sixth transmitter will be provided by Project SNOWstorm itself, now one of the world’s largest Snowy Owl research projects.

It’s a collaborative effort of over 40 researchers, bird banders, wildlife veterinarians and pathologists, donating their time and expertise to tag owls with next-generation cellular transmitters that cost $3,000 each. The transmitters weigh about 40 grams, about 1.5-3% of the bird’s weight, and attached with a backpack harness that goes over the bird’s wings but does not limit the bird’s flight or foraging abilities.

These solar-powered transmitters record locations in three dimensions (latitude, longitude and altitude) at programmable intervals as short as every 30 seconds. Incredible detail on both the daily and seasonal movements of these birds can be gleaned from the data, transmitted via cell towers, but collected and stored even when out of cell range. This information can be used to understand movement patterns, home range size, migration timing, habitat use, important migration stopover sites, foraging behavior, where they spend the summer, threats to their survival, and how they interact with other Snowy Owls.

Project SNOWstorm believes it’s imperative to better understand the Snowy Owl’s winter ecology because they breed in regions where climate change is occurring most dramatically — and because it’s now clear that the global Snowy Owl population has been badly overestimated. Recent studies put the world population at just 30,000, barely a tenth of what previously had been believed.

This also is why the Wisconsin Humane Society, other wildlife agencies and airports are going to great lengths to relocate and rehabilitate some of the Snowies, who face the same dangers that lurk out there for raptors of all kinds. Snowies wind up injured or dead from vehicle strikes, electrocution, toxins like rat poisons and mercury, and even collisions with utility lines in which electrocution isn’t a cause.

The Wisconsin fundraising effort comes in a winter that has brought what a Department of Natural Resources biologist calls “one of the largest irruptions of Snowy Owls we have documented,” and groups like WSO and Sheboygan Audubon are (or will be) holding field trips so members and non-birders alike can gain a respectful look.

These irruptions, or invasions, generally have occurred every four to five years, but Wisconsin has seen five in the last eight years, including mega-irruptions in 2013-’14 and again this winter. That’s in a state that ranks second nationally in the proportion of citizens who call themselves birders. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, a third of Wisconsin's population -- around 1.7 million people -- are birders.

But the phenomenon is bigger than that. Conservation biologist Ryan Brady, who as the DNR’s bird monitoring coordinator also pays attention to how the public interacts with these winter visitors, offers some perspective:

“In all my time working with birds no species has resonated more with the non-birding public – even more than eagles, cranes and the other white birds we tend to like – egrets, swans and pelicans. At 3 to 6 pounds, Snowies are the heaviest of all North American owls, and their bright white plumage, large yellow eyes, massive feathered feet and perhaps most significantly their tendency to hunt and move around during daylight hours, captivate even the most casual nature lover. And then there’s the remote Arctic wilderness they evoke.”

Brady also saluted the NRF for its support of Project SNOWstorm, noting that its Bird Protection Fund supports the DNR’s work in monitoring nongame species, including owls.